Originally, there were thirteen peerages in France: six ecclesiastical and seven lay. Since then the number of peerages all but exploded which generally decreased the value of a peerage - but not making it completely worthless.

Since the end of the 13th century the peers took on the role of royal officer; as such it is not a title of nobility. It soon became evident to the kings that they could tie the most important nobles to themselves by granting them peerages. Consequently, from the 16th century the granting of peerages escalated. In the ancien regime the rights that came with a peerage were primarily attached to honorific functions; it was different in England. A peer enjoyed certain privileges. These included the right to a seat in the Parlement of Paris as well as the right to be judges by their peers - meaning by aristocrats who were also peers.

The dignity attached to each peerage was dependent on the age of that peerage's creation. Note that in the following list I have only included the peerages that were still in use by the time Louis XIV ascended the throne. The year in italic is the year it was founded.

The Ecclesiastical Peerages:

Archbishop-Duke of Reims

Bishop-Duke of Langres

Bishop-Duke of Laon

Bishop-Count of Beauvais

Bishop-Count of Châlons

Bishop-Count of Noyon

The Archbishop of Paris was per definition also given the title of Duc de Saint-Cloud but was not an original peer.

The Original Lay Peerages:

Duc de Bourgogne

Duc de Normandie

Duc d'Aquitaine (later renamed to Duc de Guyenne)

Comte de Flandre

Comte de Champagne

Comte de Toulouse

The Peerages during Louis XIV-Louis XVI:

Duc d'Aiguillon (1599) - House of Vignerot du Plessis

Duc d'Albret (1556) - House of de La Tour d'Auvergne

Duc d'Alencon (1367) - Royal Family

Duc d'Amboise (1787) - House of Bourbon

Duc d'Angoulême (1317) - Royal Family

Duc d'Antin (1711) - House of Pardaillan de Gondrin

Duc d'Arpajon (1650) - House of d'Arpajon

Duc d'Aubigny (1683) - House of Richmond

Duc d'Aumale (1547) - House of Savoy then House of Bourbon

Duc d'Auvergne (1360) - Royal Family

Duc de Beaufort (1597) - House of Bourbon-Vendôme

Duc de Berry (1360) - Royal Family

Duc de Biron (1598) - House of Gontaut

Duc de Boufflers (1708) - House of Boufflers

Duc de Bourbon (1327) - House of Bourbon-Condé

Duc de Bournonville (1652) - House of Bournonville

Duc de Brissac (1611) - House of Cossé

Duc de Brunoy (1777) - Royal Family

Duc de Cardone (1652) - House of de La Mothe-Houdancourt

Duc de Charost (1672) - House of Béthune

Duc de Châteauroux (1616) - House of Bourbon-Condé, House of Mailly and Royal Family

Duc de Châteavillain (1703) - House of Bourbon

Duc de Château-Thierry (1400) - House of La Tour d'Auvergne

Duc de Chartres (1399) - Royal Family

Duc de Châtillon (1736) - House of Châtillon

Duc de Chaulnes (1621) - House of d'Albert

Duc de Chevreuse (1612) - House of Lorraine

Duc de Choiseul (1665) - House of Choiseul

Duc de Clermont-Tonnerre (1571) - House of Clermont-Tonnerre

Duc de Coigny (1787) - House of Franquetot

Duc de Coislin (1663) - House of Cambout

Duc de Coligny (1643) - House of Coligny

Duc de Coulommiers (1410) - House of Orléans-Dunois

Duc de Créquy (1652) - House of Bonne de Blanchefort

Duc de Duras (1658) - House of Durfort

Duc d'Elbeuf (1581) - House of Lorraine

Duc d'Enghien (1566) - House of Bourbon-Condé

Duc d'Epernon (1581) - House of Nogaret

Duc d'Estrées (1648) - House of d'Estrées

Duc d'Eu (1458) - House of Lorraine, House of Orléans and House of Bourbon

Duc de Fayel (1653) - House of La Mothe-Houdancourt

Duc de Fleury (1736) - House of Fleury

Duc de Fronsac (1608) - House of Bourbon-Condé, then House of Vignerot du Plessis

Duc de Gisors (1748) - House of Fouquet, then House of Bourbon

Duc de Gramont (1643) - House of Gramont

Duc de Guise (1528) - House of Bourbon-Condé

Duc d'Harcourt (1709) - House of Harcourt

Duc d'Hostun (1715) - House of Hostun

Duc de Joyeuse (1581) - House of Lorraine, then House of Melun

Duc de La Ferté-Senneterre (1665) - House of Senneterre

Duc de La Force (1637) - House of Caumont

Duc de La Meilleraye (1668) - House of La Porte-Mazarin

Duc de La Guiche (1653) - House of Lorraine

Duc de La Roche-Guyon (1621) - House of Plessis-Liancourt

Duc de La Rochefoucauld (1622) - House of La Rochefoucauld

Duc de La Valette (1622) - House of Nogaret

Duc de La Vallière (1667) - House of La Baume le Blanc

Duc de La Vauguyon (1757) - House of Caussade

Duc de La Vieuville (1651) - House of Vieuville

Duc de Lavedan (1650) - House of Montaut-Navailles

Duc de Lesdiguières (1611) - House of Bonne de Blanchefort

Duc du Lude (1675) - House of Daillon

Duc de Luynes (1619) - House of d'Albert

Duc de Lévis (1723) - House of Lévis

Duchesse de Louvois (1777) - Mesdames Tantes (shared by Madame Adelaide and Madame Sophie)

Duc de Mayenne (1673) - House of Mazarin

Duc de Mercæur (1596) - House of Bourbon-Vendôme

Duc de Montbazon (1588) - House of Rohan

Duc de Montausier (1644) - House of Saint-Maure

Duc de Montaut (1660) - House of Montaut-Navailles

Duc de Montmorency (1551) - House of Montmorency, then House of Bourbon-Condé

Duc de Montpensier (1539) - House of Orléans

Duc de Mortemart (1650) - House of Rochechouart

Duc de Nemours (1404) - House of Orléans

Duc de Nevers (1347) - House of Mancini-Mazarin

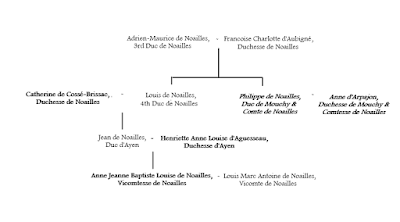

Duc de Noailles (1663) - House of Noailles

Duc de Noirmoutier (1650) - House of La Trémoïlle

Duc d'Orléans (1344) - House of Orléans

Duc d'Orval (1652) - House of Béthune

Duc de Praslin (1762) - House of Choiseul-Praslin

Duc de Penthièvre (1569) - House of Bourbon-Vendôme, then House of Bourbon

Duc de Piney-Luxembourg (1581) - House of Albert, House of Clermont-Tonnerre and House of Montmorency

Duc de Ponthieu (1412) - Royal Family

Duc de Rambouillet (1711) - House of Bourbon

Duc de Randan (1661) - House of Foix

Duc de Rethel-Mazarin (1347) - House of Gonzaga, House of Mancini-Mazarin and House of La Porte-Mazarin

Duc de Retz (1581) - House of Gondi

Duc de Richelieu (1683) - House of Vignerot du Plessis

Duc de Roannais (1372) - House of Gouffier, then House of La Feuillade

Duc de Rohan (1606) - House of Rohan, then House of Rohan-Chabot

Duc de Rohan-Rohan (1714) - House of Rohan-Soubise

Duc de Roquelaure (1652) - House of Roquelaure

Duc de Rosnay (1651) - House of L'Hospital

Duc de Saint-Aignan (1663) - House of Beauvilliers

Duc de Saint-Fargeau (1575) - House of Orléans

Duc de Saint-Simon (1635) - House of Rouvroy

Duc de Sully (1606) - House of Béthune

Duc de Taillebourg (1749) - House of La Trémoïlle

Duc de Thouars (1595) - House of La Trémoïlle

Duc de Tremes/Gesvres (1648) - House of Potier

Duc d'Uzès (1572) - House of Crussol

Duc de Valentinois (1642) - House of Monaco

Duc de Valois (1344) - House of Orléans

Duc de Vendôme (1515) - House of Bourbon-Vendôme

Duc de Ventadour (1589) - House of Lévis

Duc de Verneuil (1652) - House of Bourbon

Duc de Villars (1707) - House of Villars

Duc de Villars-Brancas (1652) - House of Brancas

Duc de Villemor (1651) - House of Séguier

Duc de Villeroy (1651) - House of Neufville

Duc de Vitry (1650) - House of L'Hospital

Comte de Blois (1399) - House of Orléans

Comte du Maine (1331) - Royal Family

Comte de Perche (1566) - Royal Family

Comte de Poitou (1315) - Royal Family

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)