The duo of the Princesse de Lamballe and the Duchesse de Polignac are usually mentioned as the friends of Marie Antoinette; generally, the three women have been depicted as forming a trio of female friendship through turbulent times. While it is true that both Lamballe and Polignac were integral parts of Marie Antoinette's inner circle, their mutual friendship seem to have been somewhat more prone to petty jealousies and rivalry.

The Savoyard princess Marie Thérèse was married into the extended royal family in 1767 when she became the Princesse de Lamballe. Being widowed at just 19 years old, she enjoyed the privileges of being a princess of the blood. As such, she was there to welcome the new dauphine, Marie Antoinette, when she arrived in 1770.

Meanwhile, Yolande Martine Gabrielle de Polastron was French by birth, but had moved in rather obscure circles of nobility before being invited to Versailles by her cousin, Diane, in 1775. It was there that she was introduced to Marie Antoinette who was said to have been immediately struck by the newcomer. Thus, Yolande was the latest edition to the little group and she would soon become well-acquainted with Madame de Lamballe.

Coincidentally, the two women shared an exact birthday - 8 September 1749. Hierarchically, however, Polignac was far beneath the Princesse de Lamballe. Not only was Marie Thérèse a member of the Savoyard royal family - and thus related to the kings of France - she was also a princess of the blood by marriage. In contrast, Gabrielle's family was old nobility but had become quite impoverished and had hitherto failed to break through into the very elite of the aristocracy.

Ideally the two women would have found a common cause in the resentment their favour with the queen brought; after all, Marie Antoinette was an extremely generous friend. Both ladies were showered in favours, positions, even money when at the height of their respective favour. While the position of Surintendante of the Queen's household was reinvented for Lamballe, Polignac was granted the post of governess to the royal children. These were two of the most prestigious positions available for women and its distribution shows both the queen's wish to benefit her friends - and their rivalry.

|

| Madame de Polignac |

Conveniently, the Austrian ambassador Mercy-Argenteau kept the queen's august mother, Empress Maria Theresia, abreast of everything regarding her daughter's life. This included her social life, and it is partially thanks to the assiduous ambassador's frequent missives to Vienna, that we are able to follow the unfolding rivalry between Lamballe and Polignac.

As early as 15 November 1775, Mercy-Argeanteau wrote:

"Her Majesty (Marie Antoinette) does not know how to reconcile the princesse de Lamballe to the Comtesse de Polignac, because these two favourites, who are jealous of each other, have been presenting the queen with respectful little complaints disguised as marks of the most loving sensitivity"

Remember that Yolande had only been presented to the queen earlier that year. Perhaps - not entirely unfounded - did Lamballe see the new-comer as a threat to her position. Undoubtedly, the queen began to spend more time with the headstrong Yolande and slightly less with the sensitive Lamballe. If Marie Thérèse did indeed feel herself slipping out of royal favour, she was not handling it well.

By May 1776, Marie Antoinette was showing clear signs of being very irritated with Lamballe who was picking fights with everyone in the queen's household. Thus, the queen turned even more to Polignac which only further exasperated the frustrations of Lamballe. As mentioned by Mercy-Argenteau, this (quite frankly silly behaviour) caused the queen to constantly having to act as peacemaker in her own household.

As time went on, Marie Antoinette continued to split her favour somewhat equally - at least outwardly. When Yolande's husband was made the queen's Premier Écuyer, the Duc de Chartres (a dear friend to Lamballe and son of the Duc d'Orléans) was immediately made governor of Poitou. Tit for tat. Yet, these attempts at keeping the peace only worked for brief periods of time.

By January 1777, Mercy-Argenteau once again reported on the state of the queen's closest friends:

"The queen often has some difficulty in keeping up the appearance of friendship between the princesse de Lamballe and the Comtesse de Polignac."

If Mercy-Argenteau was correct in his assessment (and he did have access to the queen which few others did) the relationship had become more than strained. The ambassador was personally in no doubt of the reason for this enmity. In the same letter, he wrote:

"As the latter's favour (Polignac) grows, that of the Surintendante withers away so that she has now become a bore and an annoyance to the queen"

Mercy-Argeanteau might be slightly harsh here. Marie Antoinette was not known for doing things she rarely wished to do and it would have been very easy for her to dispense entirely with the social company of the Princesse de Lamballe. Yet, she did not. As her surintendante, the queen could not escape her company but she did have the option of excluding her from social events which she refrained from doing. There can be little doubt that Lamballe - despite often being likened to an angel - was intensely jealous of her rival.

Madame de Polignac herself was entirely aware of this and - equally as petty as Lamballe's jealousies - took full advantage. As her company was increasingly considered necessary to the queen, Madame de Polignac did not rise above the temptation to "bad-mouth" Madame de Lamballe. Both Marie Antoinette and Yolande de Polastron shared a somewhat sharp sense of humour which (unfortunately) occasionally delighted in ridiculing others. It can easily be imagined that such snide comments were carefully intertwined in otherwise casual conversation in the queen's private company.

|

Mercy-Argenteau - the man who had

plenty to say of the two ladies |

While the Princesse de Lamballe was not known for her intelligence, she was clearly not unaware of the decline of her favour with the queen. The later years of the 1770s, she spent an increasing amount of time away from court, primarily for health reasons. Publicly, this was widely seen as a natural consequence of the clear change in favorites exhibited by the queen; however, when she returned, Lamballe was still welcomed into the queen's inner circle, albeit with less warmth than before. Even so, Lamballe did not surrender without a fight. Knowing the queen's near-constant search for amusement, she ensured that her well-stocked coffers offered what the royal treasury increasingly could not: balls, high-stakes gambling, operas. Alas, even these attempts had little impact as Lamballe often found herself snubbed in favour of La Polignac.

Socially, they moved in slightly different circles. Besides the all-important company of the queen, the two women drew support from separate groups at court. Whereas Madame de Polignac surrounded herself with her family members and the male members of the queen's entourage, Madame de Lamballe found support in the princes of the blood. Particularly, the Duc de Chartres was a close friend as was the Comte d'Artois. Unfortunately, this division only further added to the schism between the women as their individual supporters gladly took sides in any conflict between them.

By 1780, Mercy-Argenteau bluntly reported Lamballe's deroutement to the Empress of Austria:

"The Comtesse Jules (Polignac) has completely succeeded her rival in the affection of the queen"

Did this mean that Madame de Lamballe was entirely excluded? Not quite. Hers was the lot of previous royal favourites whose time has run its course. She was welcomed politely into the queen's circle but over the following years, the queen made no attempt at hiding her preference for Polignac. There was nothing for Lamballe to do but to accept her new position and attempt to regain her former ascendancy. For a brief period towards the latter half of the 1780s, Madame de Polignac felt briefly out of favour with Marie Antoinette. The result was a trip to London where Gabrielle basked in the company of the Duchess of Devonshire. Upon her return, things seem to have mended (perhaps she had rid herself of a noisome alleged lover, the Comte de Vaudreuil, infamous despised by the queen?).

|

| Marie Antoinette |

If Lamballe was jealous, what was Polignac? Considering the immensity of the favours she reaped from her friendship with the queen, it is possible that Yolande never truly considered Madame de Lamballe a threat to her position. The queen's generosity ensured that she had amble proof of Marie Antoinette's esteem, so maybe her somewhat backhanded comments regarding Lamballe was considered sufficient to keep her rival at bay.

While Mercy-Argenteau provides a wonderful insight into the private sphere of the queen, it should be remembered why he was at the French court. He was, first and foremost, a politician. Throughout his correspondence, he rarely refers to the two ladies solely in their own capacity. In his eyes, they each represented a different faction; each was carefully weighed and measured according to the level of threat he regarded them as. It should be pointed out that Mercy-Argenteau had continuously reported to the Empress that Polignac was the greater threat but he still would prefer if the two ladies could cancel their respective influences out. Either one - he mused - presented a threat in her own right to the queen's reputation and proper conduct. This should be kept in mind when discussion his depiction of their relationship.

It is highly unlikely that the queen considered her relationships with the same political cynicism. To be sure, she might have found Madame de Lamballe slightly boring after a while, but she never ceased caring for her first friend in France. When Madame de Lamballe fell ill at her private estate, the queen assiduously inquired after her and never excluded her entirely from her private apartments.

What the queen did do, however, was almost as mortifying. As Madame de Polignac's influence grew, so did the number of relatives of hers who surrounded the queen. It was noted by Madame Campan (another insider to the queen) that Lamballe had been greatly concerned at the rapidity with which Madame de Polignac gained the queen's favour. Her concern turned to mortification when the queen began shutting herself in her private apartments. This, of course, had always been the queen's tendency, but hitherto, Madame de Lamballe had been on the other side of the door. While not exiled from the queen's presence, she was not invited to the gatherings when they consisted of Madame de Polignac and her family and friends.

The possibility exist that Mesdames de Polignac and de Lamballe were not so irreconcilable as observers such as Mercy-Argenteau mused. Both would have known full well that royal favour was fleeting. Considering that they seemingly kept any quarrels somewhat private - very few contemporary sources noted any concrete examples of outright infighting - it is possible that their relationship had developed into one of necessary tolerance rather than blatant enmity. After all, by the mid-1780s, they had both been in the queen's company for ten years and neither had succeeded in formally ousting the other. Perhaps, then, it was better to seek the queen's good graces by more subtle, courtly manners.

While neither Lamballe nor Polignac have left written testament to their personal feelings for one another, their outward conduct tells its own tale. Neither woman visited the other at their private estates - not even following an illness or an accouchement. The separation of the Polignac-clan from Madame de Lamballe's company is a further indicator that they did not see eye to eye. Finally, whereas Marie Antoinette wrote them both assiduously, they did not seem to have corresponded.

|

| Madame de Lamballe |

When the revolution broke out, once again the two ladies found themselves in completely different situations - but with the same outcome. By the end of 1793, Marie Antoinette, the Princesse de Lamballe and the Duchesse de Polignac were all dead.

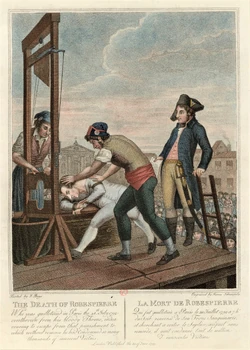

The first to succumb to the violence of the time was the Princesse de Lamballe. Having been hauled before a tribunal, her captors demanded that she swore an oath to liberty and denounced the royal family. She agreed to the former but utterly refused to denounce her friend. Upon leaving the courthouse, a furious mob set upon her and massacred her. Stabbed, beaten and decapitated, her head was placed on a pike and placed outside the queen's window. The queen herself died on the guillotine just a month later.

This left Madame de Polignac. By the time of her erst-while rival's grisly death, she was long gone. Her unpopularity had reached almost unprecedented heights and she had fled France and gone to Vienna, the birthplace of Marie Antoinette. There, she died in December 1793 of an unknown illness.

Mesdames de Lamballe and de Polignac had certainly been rivals for the queen's affection and the bounty of royal favour. Yet, they had also shared years of their lives together with their mutual friend. None of them survived the Revolution and thus their relationship remains inextricably tied with their lives at Versailles.