The tightly corseted, widely panniered silhouette of a female courtier has become synonymous with the extravagance of the 18th century. While the robes à la Française, à l'Anglaise and à la Polonaise are the variants of female dress typically referred to, the epitome of Versailles-elegance is the grand habit.

Interestingly, the grand habit's roots were not the 18th century but rather the preceding 17th century. The term "habit de cour" itself was slightly longer taking hold; by 1708, it was still a fair new concept. Over the decades (only interrupted by the revolution), the silhouette grew in size. The sheer volume of the skirt increased drastically as the 18th century marched on, to the point of the borderline ridiculous. Still, the grand habit's "building blocks" remained the same: pannier, petticoat, corset, bodice and train. Added to that were the essential accessories such as the chemise, the engageants (lace trimmings of the sleeves) and various adornments to the gown itself.

| This Mantua is a good example of how the grand habit started out during Louis XIV |

Briefly put, the grand habit de cour was the formal attire of a noblewoman. As such, it was the required "uniform" for the larger events such as coronations, royal weddings, diplomatic meetings, bals parés etc. Given its purpose, it is hardly surprising that the grand habit were created from the most lavish - and expensive - articles of clothing. The original purpose appear to have been a tad more universal; for instance, Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate wrote in 1702 that everyone who appeared before herself or the king were in grand habit. This indicate that at this time, it was still a court staple rather than the rare requirement for special occasions.

The grand habit was a cumbersome affair to wear. As mentioned, it consisted of several large pieces of clothing including a train, a skirt, a stiff bodice and a petticoat. Typically, their backs would be cut like a robe à la Française, that is, with two pleats running from the shoulders to the ground.

While the grand habit was designed for splendour, very little thought had been given to comfort. The corsets used for this type of dress was the rigid, boned corsets typically associated with the high society of the time. For the queen, this would usually be made from whalebone. The bodice itself would be remarkably low-cut - one can only surmise at the irony of a society which frowned on an exposed ankle but dictated a very deep cleavage.

While the train was detachable, it was often very heavy and could be quite long - however, the length depended on the rank of the lady wearing it. A length of about 4 meters was not unusual for the higher ranking ladies which must have made it a nightmare trying to navigate between the many, varying trains without stepping on one. The length of the train also presented difficulties for the wearer; it was one thing when moving straight ahead, but turning around or even backing was quite a challenge.

|

| As can be seen from this specimen, the panniers assumed ridiculous widths |

The grand habit was a status symbol; as such, its use was not permitted for everyone. Only ladies who had been officially presented to the royal family were entitled to don the ensemble. The only exceptions were the dames de chambre to either the queen or royal princess - yet, they were prohibited from using a train. The public transformation of a woman from an unpresented lady to an official, presented lady always occurred in a grand habit. The lady to be presented was heavily adorned with everything to symbolise her family's standing - naturally, this was a grand habit.

The Baronne d'Oberkirch has left a vivid description of the grand habit ordered for her own presentation at Versailles in the 1780's. By this point in time, the panniers were massive which consequently required immense amounts of fabric. The Baronne's choice of fabric was an expensive gold brocade which was heavily embroidered with a myriad of flowers. While she did receive a good many compliments, she also admits that the gown was unbearably heavy.

|

| Trimmed with metallic lace thread |

When looking into the make-up of the royal versions of the grand habit, it is little wonder if the dress was terribly heavy. Besides the usual meter upon meter of fabric, it was very en mode to have gemstones - particularly diamonds - sewn into the bodice. In her younger years, Marie Antoinette's grand habits were often pale colours - even entirely white - with just such adornments. Pearls, too, were a go-to for ladies of the court. Marie Leszczynska were no less richly adorned than her successor. Several of her state portraits show the queen in rich, extravagant concoctions adorned with everything from gemstones to golden thread.

It was also a remarkably cold outfit to wear. While the amount of fabric used would typically give the impression that the wearer was well-protected against the cold, the intricate concoction beneath the gown offered little protection. Particularly the extremely wide panniers made it all too easy for cold air to seep up under the skirt - and the only barrier from there was the thin chemise and the corset. For the most parts, the legs were fair exposed to such breezes as chemises were not floor-length. Added to that was that the fabrics were not chosen for their insulation function; no wools were used. Brocade was a popular staple but even the heat-retaining qualities of silk were not always enough.

|

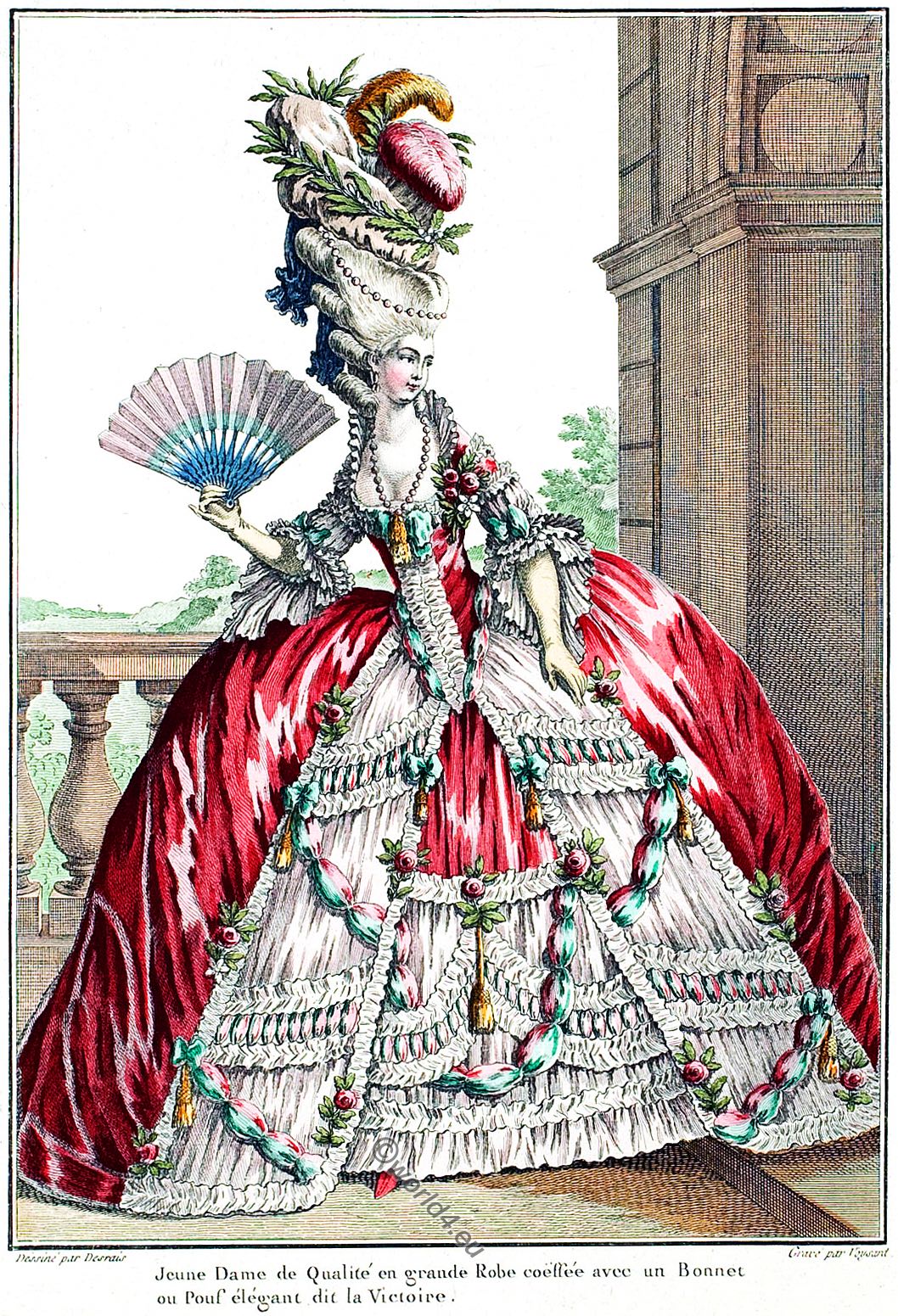

| A young lady in a grande robe - notice how tight the corset is and how low-cut the bodice |

The panniers certainly added their fair share of weight to the ensemble. By the mid-18th century they could reach up to 3 meters in width! Typically, the fabric of all the pieces matched each other. The opportunities in the trimming department were endless: bows, jewels, ribbons, flowers (real and artificial), buttons, knots, flounces - whatever the customer desired was possible.

The sleeves were the length of a modern 3/4 sleeve - it typically ended just above or below the elbow. Over time it became the accepted tradition of having three layers of exquisite lace for the engageants.

|

| Marie Leszczyńska in grand habit |

The cost of a grand habit could be ruinous. According to Garsault, no less than three different craftsmen were needed to fully achieve the goal. A tailor was hired to make the train and bodice, a coutière for the petticoat and a so-called marchande de modes to add all the vital trimmings. Besides the obvious expense for the labour involved, the cost of material was immense.

|

| The type of grand habit popular during Marie Antoinette |

Marie Antoinette's grand habits often featured a personal passion of hers: flowers. Particularly the fleur-de-lys was a favourite for the official state portrait. However, despite the epitaph of "queen of fashion", Marie Antoinette was less than thrilled with the concept of the grand habit. Her personal taste developed towards the more simple and even once declared to Louis XVI that the grand habit of a lady was "obsolete and unbearable". She entreated the king to allow the ladies to reduce the size of their panniers for royal functions which he agreed to.

The need for the king's approval to alter the restrictiveness of the grand habit truly demonstrate how the gown had become the almost the state sanctioned uniform for ladies of the court. Wearing the gown was not merely the privilege of the aristocratic ladies - it was their duty. It speaks volumes that the queen herself - and one who adored fashion herself - had to bring it to the king's attention to achieve some change.

Gorgeous! I read somewhere that the first presentation gown was black, and could not be worn again (thus increasing the latent costs) - but I can't seem to find the article again. Did I dream it? You'd have thought there'd be more exactant gowns and fashion plates in black if it were true.

ReplyDeleteOh, I found it. M. Garsault in 1769 Encyclopedia Description des Arts et Metiers

ReplyDelete