Born on 10 November 1704 to the Margrave of Baden-Baden and Sybille of Saxe-Lauenburg, Auguste was the only surviving daughter. Just three years after her birth Auguste lost her father and her mother became regent of Baden-Baden.

Generally, Auguste's childhood was a good one. Her mother had a great love of the arts and cultivated them at her court. Thus, Auguste grew up in an environment filled with not only beautiful exteriors but poetry, literature and music.

As the only daughter, it was necessary to find a suitable match for her. Eventually, two candidates emerged as the best possible choices: Alexander Ferdinand of Thurn und Taxis and Louis d'Orléans, Duc d'Orléans. The former would have kept her daughter in the German sphere and would have established her as a wealthy woman. The latter was also wealthy but came with the further advantage of making peace with France. Auguste's father had been opposed to Louis XIV which had resulted in the invasion of a French army. By marrying off her daughter into a house of France the two could establish a more lasting peace.

Meanwhile, in France, the prospective mother-in-law, Françoise Marie de Bourbon, was curious about this princess of Baden-Baden. According to the Duc de Richelieu, she sent a trusted servant to spy on her and report back. Apparently, he sent a good report and Françoise agreed to the match.

Meanwhile, in France, the prospective mother-in-law, Françoise Marie de Bourbon, was curious about this princess of Baden-Baden. According to the Duc de Richelieu, she sent a trusted servant to spy on her and report back. Apparently, he sent a good report and Françoise agreed to the match.

Auguste, however, was more inclined toward Alexander Ferdinand. The Duc de Bourbon would also have been pleased had she remained on German soil. This was not due to an aversion towards Auguste but rather that the Duc de Bourbon was not a friend to the Duc d'Orléans and sought to irritate his mother as much as possible.

In the end, her mother decided on the opposite candidate and Auguste was married off to Louis d'Orléans on 23 July 1724. Her dowry was not grand but the house of Orléans was already very wealthy and made no fuss. After all, it was not wealth that had decided in her favour but her appearance, behaviour - and Catholicism.

|

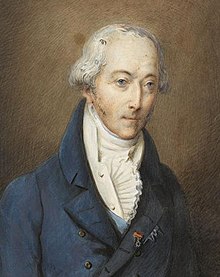

| Auguste |

In the end, her mother decided on the opposite candidate and Auguste was married off to Louis d'Orléans on 23 July 1724. Her dowry was not grand but the house of Orléans was already very wealthy and made no fuss. After all, it was not wealth that had decided in her favour but her appearance, behaviour - and Catholicism.

Once she arrived at Versailles, Auguste found herself one of the leading ladies at court. There was no queen and no dauphine - consequently, she and her mother-in-law (Françoise Marie de Bourbon) were the highest-ranking ladies. Despite having originally been opposed to the match Auguste did not enter her marriage with an aversion towards either her husband or her new country. As it happened it would seem that the match was very lucky in that they were considered to be very well matched. Her charm quickly won her the popularity of her fellow courtiers and her wit and piety was praised by her contemporaries.

When Louis XV married Marie Leszczynska she had to step one step down in the hierarchy but this does not appear to have caused Auguste any vexation. Instead, she spent her time either at Versailles or at the Château de Saint-Cloud. Not long after having signed the marriage contract Auguste became pregnant. For her first accouchement she remained at Versailles where she gave birth to a son and heir expected of her in May 1725.

|

| Auguste with her son |

Auguste had already done her duty and provided her husband with a son but quickly became pregnant again. Once more she had planned on remaining at Versailles but her mother-in-law had other ideas. Françoise Marie insisted that her daughter-in-law travel to Paris for her lying-in. Obediently, Auguste entered her carriage - while heavily pregnant. As it happened labour began during the journey which meant that she had to make a pitstop at Sèvres on 4 August. Nevertheless, she continued on to the Palais-Royal where she was delivered of a daughter.

It did not take long to realize that something was wrong. Auguste became violently ill following the birth and continued to deteriorate. It is possible that she suffered from puerperal fever - meaning that a part of the placenta had not come out. Whatever the cause the result was fatal; Auguste died on 8 August 1726 - at just 22 years old.

Her husband was distraught and refused to remarry; he entered into a long period of mourning. He was not the only one who mourned her loss; it was that her death was "the universal regret of France".

It did not take long to realize that something was wrong. Auguste became violently ill following the birth and continued to deteriorate. It is possible that she suffered from puerperal fever - meaning that a part of the placenta had not come out. Whatever the cause the result was fatal; Auguste died on 8 August 1726 - at just 22 years old.

Her husband was distraught and refused to remarry; he entered into a long period of mourning. He was not the only one who mourned her loss; it was that her death was "the universal regret of France".