The fate of Marie Louise d'Orléans is a remarkably sad one. Being the eldest daughter of Philippe, brother to Louis XIV, she was destined to make a glorious match when she became old enough to marry. For years, it had been speculated that she would marry her first-cousin, the Grand Dauphin, which would make her the future queen of France. As she grew older, Marie Louise herself became quite enamoured with the idea of marrying the heir to the throne - and likely the idea of becoming queen herself.

The union would not have been unthinkable despite their very close familial relationship. Louis XIV himself had married his own first-cousin, Marie-Thérèse, and it would also serve as a means of uniting the two branches of the family on the throne. Their ages, too, were compatible. Marie Louise had been born just a few months after the Grand Dauphin and they had grown up together.

Thus, when the 17-year old Marie Louise was summoned to the presence of both the king and her father, the Duc d'Orléans, in July 1679, she likely expected to hear news of a forthcoming marriage. However, her fate was not to become queen of France - but of Spain.

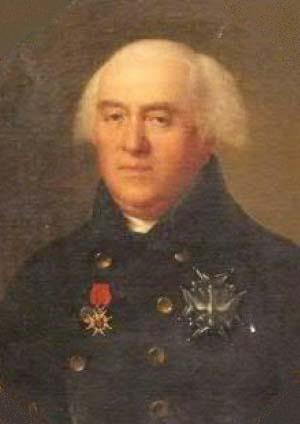

|

| Marie Louise at the time of her marriage |

Louis XIV wished to place his niece on the throne of Spain which required her to marry Charles II. The bride-to-be was absolutely distraught. Having been convinced for years that she would marry her cousin Louis, this development brought a whole onslaught of startling consequences. For one, she would have to leave her family - permanently. If she had married the Grand Dauphin, she would have had the privilege of remaining in her native country with her own family for the rest of her life. Now, she was to leave France behind immediately after the wedding.

Marie-Louise is said to have protested fiercely against the marriage to the best of her abilities. This included beseeching her all-powerful uncle, Louis XIV, to allow her to stay in France. Yet, there was not budging the Sun King who assured her that by making her queen of Spain, he could not have done more for his own daughter. Marie Louise is said to have responded by retorting: "No, but you might have done more for your niece". It was even said that she threw herself at the feet of the king, begging him not to make her go. Alas, sacrificing a niece was easily done for the good of the realm.

|

| Proxy marriage |

The bridegroom himself was not exactly a promising prospect either. Despite having the decided advantage of being king of Spain, Charles II was the result of generations of intense inbreeding and is thought to have suffered from several debilitating disabilities as well. The combination was not attractive for a young woman who was already determined to marry someone else. Her future husband was notoriously unattractive and prone to illnesses; while it was suggested that he was feebleminded, there is little to suggest that that was actually the case. He was also an avid hunter which would have been impossible if he had been entirely disabled.

The behaviour of the Spanish king was erratic, at best. Having become notorious for his fits of rage at his own courtiers, he had become besotted with his future wife from the moment he received her portrait. He continued to be devoted to her but also came to resent that she never conceived a child.

Another dreaded aspect was the extremely restrictive Spanish court. Whereas Versailles was ruled by etiquette, Madrid was strangled by it. The lives of the monarchs were so isolated by the countless prohibitions on direct contact with them that Marie-Louise would inevitably have a very lonely life. Furthermore, any carefree private life was entirely ruled out.

The preparation for the big event was a mixed affair. While the bride was obviously downcast and often seen weeping, her father relished both the idea of having a queen for a daughter and being able to equip her with a splendid trousseau. Meanwhile, the bride continued her outward display of grief at what she considered a terrifying fate. The wedding by proxy took place on 30 August 1679; the couple was married in person on 19 November that year.

|

| Marie-Louise as queen of Spain |

Upon her final goodbyes to her family, she was once again reminded of the purpose of her new life by Louis XIV himself; the king informed her that it would be the greatest unhappiness if she ever saw France again.

Undoubtedly, this did little to comfort the teenage-bride and indeed she never did see her native country again. Finding a devoted husband in Charles II, she nevertheless suffered from his sterility - which was blamed on her - and the suffocating life at the Spanish court. Besides being obliged to witness the Inquisition perform its terrible practices, she was prevented from even looking out the windows of the royal palaces by etiquette. Her every move was scrutinized but the monotony was not broken up by the opulent parties of Versailles. Instead, the court of Madrid was oppressive and dour. It was not long before Marie Louise's fears for her future seemed to come true; after ten years of gilded solitude, Marie Louise died suddenly at just 26 years old.