The nobility was neither the only nor the largest population group who were targeted by the revolutionaries. As paranoia grew across the increasingly chaotic first days of the new republic, anyone who was considered anti-revolutionary was deemed an enemy. On occasion, such persons were targeted due to their association with the former royal court of Versailles - despite not being amongst the higher nobility (or any nobility) themselves.

The Tribunal which sentenced both Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette to death, kept a meticulous record of its victims - they can hardly be termed anything else, as the Tribunal itself issued a compiled list of those executed by it. As could be expected, the reasons given for the Tribunal's guilty verdict is ambiguous at best. "Counter-revolutionary activities" or "conspiracy" are used on numerous occasions but without any further explanations as to exactly what those activities were or why they were considered to be anti-revolutionary.

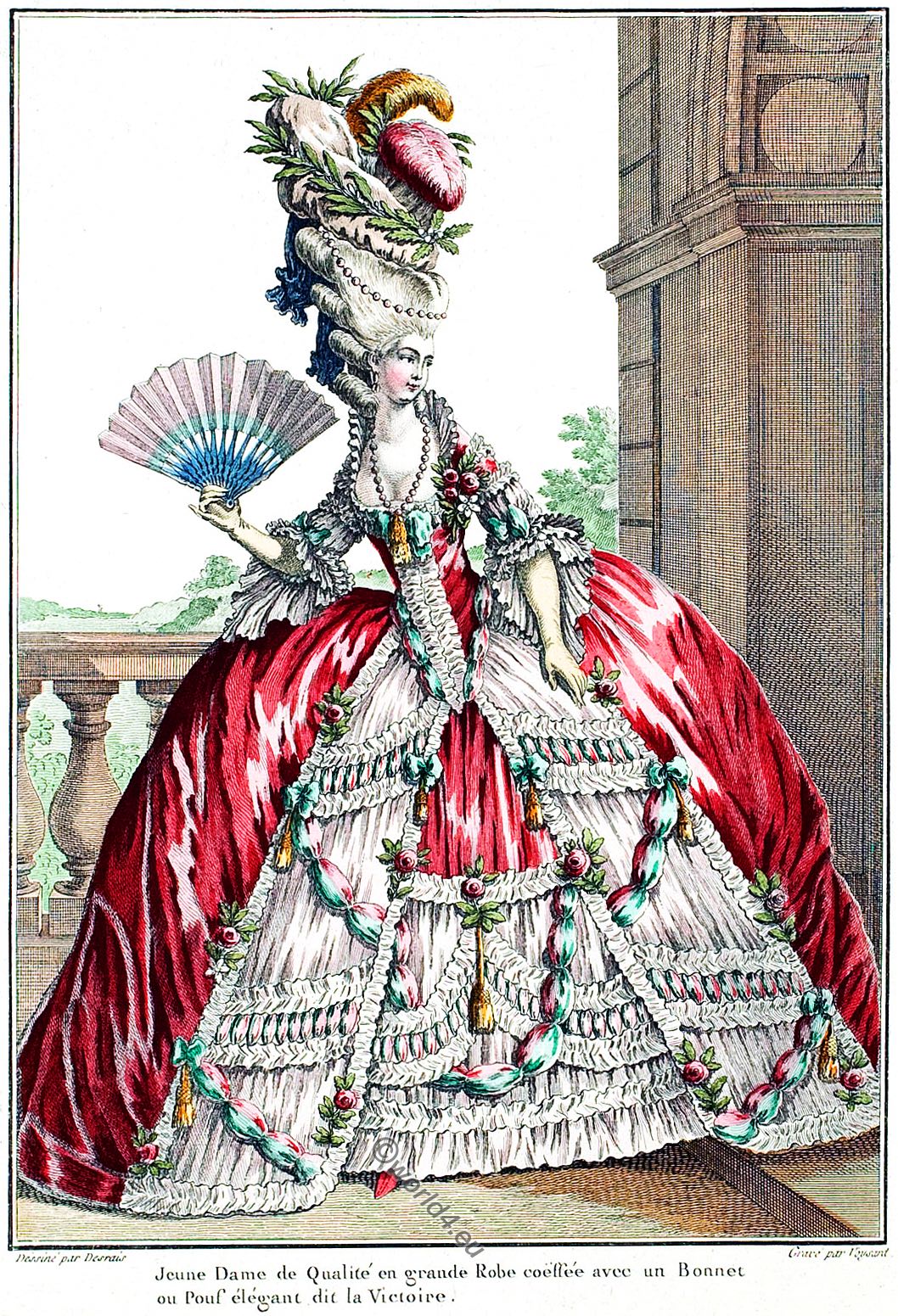

|

The executioner shows off the severed head

as proof of death to the crowd |

Death by Employment: Servants in the Royal Households

Nicolas Pasquin had served Madame Élisabeth as her valet-de-chambre; he was accused of having used his house to plot "an assassination on the French people" in 1792 - apparently, the Tribunal conveniently forgot that he, too, was of the French people. He was guillotined on 6 February 1794.

Like Nicolas, Étienne-Claude Marivetz had served the royal family in a very periphery manner. He had been an écuyer to Mesdames Tantes and was brought to "trial" for having participated in the alleged conspiracy by the then-late king and queen. Although it is not mentioned how Étienne-Claude played any part, he was still found guilty and beheaded on 25 February 1794 at the age of 65.

The 42-year old Denis Joisel worked as a guard of the nationally-owned forests - likely a forester who prevented poaching of wood - but his attachment to the court was far vaguer. It is merely mentioned that he had served the household of Monsieur, the king's eldest brother (later Louis XVIII). That would likely have made him a colleague of P. Tissère who had been the Comte de Provence's bodyguard.

Dominique Laffilard had connections to two royal households. Initially, he had been employed by the Comte d'Artois as a cook before being moved to the Comte's son's household. This first son of his generation, the Duc d'Angoulême, received quite different services from Dominique. Despite having previously been a member of the kitchen staff, Dominique was transformed into a sort of cashier for the new addition to the extended royal family. Dominique was 69 years old when he was guillotined in 1794.

Another member of the Comte d'Artois' household was a man simply named Carbillet. The then-52 year old had worked as a carpenter before the revolution. He was accused of having aided the royal family and attempted to restore the monarchy; for this, he was guillotined.

Even the coiffeur to the young Madame Royale was hauled before the Tribunal who sentenced the 34-year old to death. The same fate awaited the 60-year old former écuyer to "the late Dauphine"; likely this means Marie Josèphe, mother of Louis XVI, as well as M. Duchesne who served as the Comtesse de Provence's intendant.

Such a vague accusation of conspiracy came in handy as a catch-all for anyone who had had even a minor role at court. Noël Deschamps (40 years old) was a lawyer who was executed 1 March 1794 for having been "complicit in the conspiracies which existed at the court of the tyrant". In other words, he had somehow been linked with the court - again, the how, where, when or why is entirely omitted.

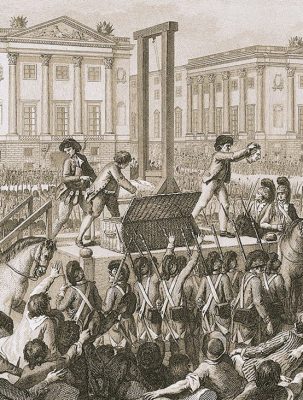

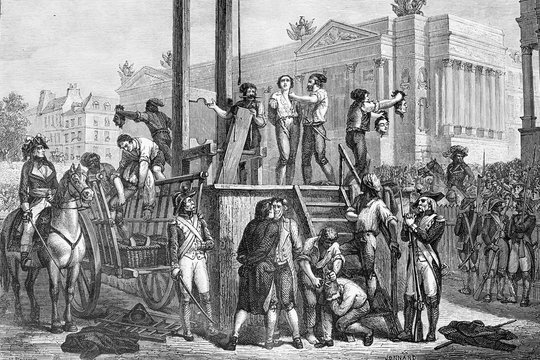

|

An execution on the Place de la Révolution -

most of the victims of the Tribunal were executed

here |

Serving the King

From the time the royal family was brought back to Versailles from their failed escape attempts at Varennes, any show of loyalty to the sovereigns was considered treason. Even something as simple as wearing a symbol of devotion to the king was enough which François-Étienne-Joseph Champleury found out at his own expense. His execution on 3 March 1794 was justified by him having worn just such a symbol of "antipathy" towards the French people. Even having once guarded the king was given as the sole crime of 44-year old Louis Étienne Tenailles Chamton who therefore met his end on the scaffold.

18 March 1794 saw the execution of several people including Jean-Rabaud Lafardie who had served as the king's secretary. This was not the king's personal secretary but rather refers to a clerical position within the king's massive household. It is unlikely that Lafardie ever worked directly with Louis XVI himself.

Having acted as a banker to the court, Jean-Joseph Laborde was 70 years old when he was found guilty - of what is unclear as it is only his connection to the court which is stated.

On occasion, the Tribunal had to go even further back in time to find a connection to the court. Marie-Marguerite-Geneviève-Victoire Lemesle was the wife of a man named simply as Boulaud. He had served as maréchal-de-logis which meant that was attached to the department of the king's household which dealt in arranging lodgings for the court. However, he had not served Louis XVI but Louis XV - by this time, Louis XV had been dead for 20 years.

Jacques-François Descombiés is mentioned as having been a page in the king's chamber during Louis XVI's reign. At the time of his execution in the summer of 1794, he was 66 years old. Another page (albeit not of the chamber) was the 48-year old E. Jardin who had been born in Versailles.

A Monsieur Béguin Perceval had served the king's passion for hunting at Compiègne. Here, he had been a so-called lieutenant of the hunt from 1787-1788; particularly, he was responsible for the wolf-hunt which had all but faded from fashion at this point. This meant that it was typically used as a form of "pest control" when the wolves came a bit too close to the country villages.

It appears that particularly men who had served in the king's military household was targeted - perhaps the new regime was threatened by their military experience? Amongst the many former guardsmen or even officers were Langlois de Rezy (46 years) who had been a lieutenant in the king's French Guard. He was accused alongside his brothers and their wives for having correspondence with the enemy and embezzlement. They were executed on 1 May 1794.

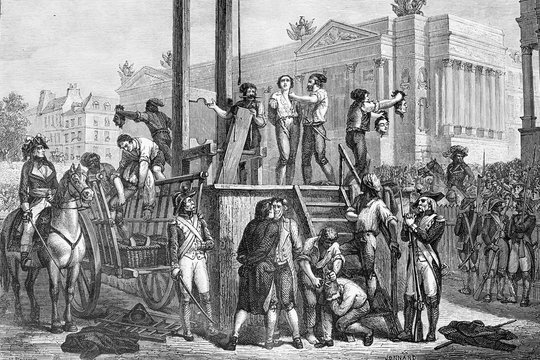

|

Those headed for the guillotine were taken

there by open cart |

P. L. Bertrand had been an officer in the Gobelet of the king's household - this department took care of the king's beverages. He was charged - and sentenced - alongside another former member of this department: J. C. Brenon who was head of the department. Amongst the charges laid against them was that of spreading misinformation and aiming at reinstating despotism.

Other members of the king's household who were executed by the Tribunal included his children's master of arms (Rousseau - not the philosopher), governor of the royal pages (Dalvinart), inspector of buildings (Pelchet), valet (Lambrequet), head of the Gobelet and even Louis XV's 68-year old page, Louis Bernard Descours.

Lastly, the head of the Menus Plaisirs stands out amongst the hundreds of condemned. Papillon de la Ferté authored an minute account of his tenure as head of this prestigious royal household. It is odd to imagine that the same man who had been so concerned with organising private concerts or large operas would later have far more serious matters on his mind. Denis-Pierre-Jean Papillon de la Ferté was executed on 7 July 1794.

Serving the Queen

Marie Antoinette was likely the most hated person in France at the time of her execution. Even two years after her death, association with the late queen was sufficient to land someone in hot water - even if they had never met the queen in person.

One such was Gabriel-Charles Doyen who had been one of the many cooks employed in the queen's kitchen. He must have entered her service as quite a young man as he was 31 years old when he was executed.

The Unknown Aristocrats

Besides the more prestigious names of the kingly couple and other well-known personages - including Madame du Barry and the Duc d'Orléans - several other ex-nobles were sentenced to death by guillotine by this very same tribunal. Interestingly, the tribunal often dealt with people who were of noble families but who were neither of the high nobility nor even the "nuclear" family of their name; typically, they would be relatives whose familial connection was typically enough for them to be considered anti-revolutionaries. This was also the case when the persons in question were neither rich, powerful nor famous - like Anne-Joseph Lauloup who was listed as "noble" but worked as a doctor. Like their bourgeoisie counterparts above, they were guilty by association with the nobility.

Touissant-Jean Duplessis Grenedan was a 29 year old man who shared a surname with the Duc de Richelieu. Likely he was a distant relative but was not rich enough to sustain himself without supplementing income. Thus, he served as a navy captain and was accused of having corresponded with unsavory types. He was guillotined on 16 January 1794.

The 23-year old Comte de Béthune-Charost was amongst a larger group of ex-courtiers who were accused of conspiracy against the new regime. He was joined by the Comtesse Fargeon and the Marquis P. A. G. V de La Tour du Pin Gouvernay. All were executed in April 1794.

The 46-year old Étienne-Thomas Ogier Baulny was caught with his 14-year old son and their bodyguard when they attempted to flee France. Forcefully, they were taken back to Paris where their attempt at escape was considered enough for the Tribunal to find them guilty. Étienne - and likely his son and bodyguard, too - was executed on 31 January 1794.

A potential relative to Étienne was Claude-Jacques Ogier who had served as a counsellor to Louis XVI. By 1794, Claude-Jacques was 73 years old and was executed on 1 February 1794.

Claire-Magdeleine Lambertie was accused of keeping up a correspondence with the intensely hated Polignacs whom she was also supposed to supply with money. Her husband had been secretary to the king which immediately linked her to the court. She was executed on 28 March 1794. She was not the only one with connections to the Polignac-family. Louis-François Poiré (36) had been a servant in the households of the Talleyrand family before being hired by that of the Polignac. Like Claire, he was guillotined in the Spring of 1794. His crime was having corresponded with the English.

Jean-Jacques Baillard, Comte de Trousse-Bois had thoroughly distinguished himself through his military service to the point of being granted the post of maréchal de camp. As such, he served as colonel of the Angôuleme-regiment; he was likely still in this position when he was accused of conspiracy which led to his death on 8 February 1794.

Jean Rouganne de Barodines was 52 years old when he was executed in the early Spring of 1794. He had not only been an aristocrat but also a knight of the Saint-Louis; he had served as a gendarme in the king's guard.

L. A. F. Bongare d'Apremon was a ci-devant marquis who was wealthy enough to live off of his revenues; these were largely subsided by his post of Grand Bailiff of Gisors. He was executed in 1795 at the age of 68.

M. A. Lévis was likely a relative of the Lévis-family; he was noted as having previously been a Comte as well as a Chevalier de Saint-Louis. He was condemned alongside the former Marquis C. A. C Choiseul Lebaune in 1794. The two men were 58 and 62 years old respectively.

A tad higher up the ladder was the former Minister for War, Louis-Antoine-Athanaise Loménie.

|

Notice the cart to the left - once it had been used to carry the

condemned to the guillotine, it could handily be used to remove

their bodies

|

These were often members of the noblesse de robe which was made up of the nobility who manned the judicial and political system of the Ancien Régime. Unlike the noblesse d'épée, they were often of more recent creation but had an uncanny ability to create remarkable fortunes in a few generations. This meant that they could even marry into the older nobility which had happened to such an extend by the 1790's that the two spheres of nobility had practically merged.

One of these main families was that of Lefebvre d'Ormesson. A member of this family - Anne-Louis-François-Paul - had followed in the family's footsteps and worked as a president of the Parisian Parliament. A colleague of his was H. J. Poulet who had been a councillor in the Metz Parliament. Both were executed in 1794 and both were considered to be of the noblesse de robe.

Others were more vulnerable due to their position in society. Widows with no surviving (male) relatives were often brought in and charged as associates to a crime based - apparently - on the connection of their husbands. Their actual, personal guilt is extremely doubtful as no official charge is necessarily given. That was the case for the 23-year old Camille-Thérèse Lepelletier Rozambo who lived in her father-in-law's house. Those are the only pieces of information given to justify her execution - that and the fact that she was married to the 34-year old Château-Brillant who had served as a captain of a royal cavalry regiment.

A similar case was that of the widowed Marie-Victoire Rochochoir whose husband had been a brigadier in Louis XVI's guard. He had also held the title of Vicomte. Like Camille, she was charged conspiracy - they were likely executed together as they were accused of the same conspiracy. These two women were young but that cannot have been said for the widow of F. Goursac. Simply termed T. Thomas, she was 80 years old when she was beheaded.

Grand Relatives

The 40-year old Anne-Alexandrine-Rosalie La Rochefoucauld shared her surname with one of the greatest families in France which appears to have been her primary crime. Of course, she, too, was accused of a "frightful conspiracy" but no further details are given - except her date of execution: 9 March 1794.

Antoine Brochet (called Saint-Prest) was only 25 years old but had already served Louis XVI as a guardsman before the revolution which would mean that he was a teenager at the time; he was executed for having aided and abetted - and even authored - conspiracies against the new republic.

Scions of some of the greater families of France were perfect targets - they represented the old order and their familial ties made it easy to attribute some sort of connection to higher-ranking family members. It also made any alleged conspiracy appear to run deep, almost like an ingrained trait in the aristocracy. Once such "conspiracy" counted several members of notable families including P. Laval-Montmorency (25 years), L. M. Saint-Maurice (38 years, ex-prince), J. C. Guthenoc Rohan Rochefort (24 years). They were executed together.

|

The very blade which beheaded Marie

Antoinette |

Serving the aristocracy

It was not only those who had served the royal family who became objects of interest but those who had offered their services to the leading aristocracy as well. One such was a man by the name of L. Armand (61 years) who had been in the household of the Duc de Mortemart. However, he is also stated as having been a winemaker which indicate that it might be some years since Armand had actually served the aristocracy.

The 49-year old Moreuil had served as maitre-d'hotel to the Comte de La Marck who himself had emigrated. After the fall of the Ancien Régime, he had taken employment for the newly-formed state. He was condemned to death on charges of having forwarded money to the enemies of the state.

A more odd destiny was that of J. Mordok who had been born in Edinburgh but somehow made his way to France where he found employ in the household of the Montmorency-family. He served as a valet-de-chambre in this household before moving to that of the Prince Pownia. He was executed alongside several other English-born soldiers who had somehow deserted the English army for the French one - including a young man of just 18 years.

Even a rather unknown aristocrat such as the Comte de Sénéchal was not considered beneath the notice of the Tribunal. J. Hypolythe Curton was just 18 years old when he was sentenced to death; he served as a servant to the Comte.

Thus, several more well-known surnames made their way into the registers of the Tribunal including those of Damas, Hautefort, La Baume, Lévis etc.

With the death of Louis XVI, the Tribunal turned its attention towards those who still showed loyalty to the new child-king, Louis XVII. Consequently, several people were executed from the middle of 1793.

The Aristocrats

Naturally, the king and queen are the most famous victims of the Tribunal but they were far from the only ones of the higher nobility who were sentenced by that institution. Amongst the other members of the aristocracy who were guillotined on the orders of the Tribunal were:

Élisabeth de Bourbon, Princesse de France and sister to Louis XVI - 10 May 1794

Béatrice de Choiseul-Stainville, sister to the Duc de Choiseul and duchesse de Grammont - 17 April 1794.

Paul Marie Victoire de Beauvilliers, Duc de Saint-Aignan - 25 April 1794

Gabriel Louis François de Neufville de Villeroy, Duc de Villeroy - 28 April 1794

Philippe de Noailles, Duc de Mouchy - 27 June 1794

Anne de Boufflers, Duchesse de Biron - 27 June 1794

Marquis de Polastron, Comte de Polastron (father of Madame de Polignac) - 27 June 1794

Anne d'Arpajon, Comtesse de Noailles (nicknamed Madame Étiquette by Marie Antoinette) - 27 June 1794

Charles Alexandre d'Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace, Prince d'Henin - 8 July 1794

Catherine Françoise Charlotte de Cossé-Brissac, Duchesse de Noailles - 22 July 1794

Louis-Armand-Constantin de Rohan, Duc de Montbazon - 27 July 1794

Marie Louise de Laval Montmorency, abbess - 27 July 1794

Louis Joachim de Potier, Duc de Gesvres - 7 July 1794

|

| Execution of Madame Élisabeth |

If you want a post listing all the ex-nobles who were executed by order of the Tribunal, let me know in the comments!