The reign of Madame de Montespan as the king's official mistress is widely celebrated as the golden age of the king's court. The union produced several children who would later be legitimised and - rather forcefully on behalf of the king - integrated into the families of the princes of the blood. The fate and disputes regarding these "bastards" (as Saint-Simon continuously called them) caused a headache which would plague the next generations as well.

While the lives of Madame de Montespan's children out of wedlock are well-known, she happened to have had two legitimate children by her husband: Marie Christine and Louis Antoine.

Marie Christine de Pardaillan de Gondrin was the first-born child of the newly married Madame de Montespan. Her birth - on 17 November 1663 - took place a little over nine months after her parents' wedding, so she much have been conceived fairly quickly. Due to her father's outrage at his wife's position as the king's mistress, Marie Christine and her brother was removed from court and taken to the country estates of the Marquis de Montespan.

Very little is known of Marie Christine's life in the country; she likely received the usual rudimentary education reserved for young ladies of the nobility. She was present for the mock funeral which her husband hosted for her mother and also lived to see the annual memorials for her (still very much alive) mother. Exactly how much the young girl understood of her parents' situation is not clear as she does not appear to have left anything behind. If her father had envisioned a marriage for her those plans never materialised. Marie Christine died at an unknown date in 1675, at 11-12 years of age.

Louis Antoine was the only son and heir of the Marquis de Montespan who consequently focused his attention on him. He and Marie Christine both grew up at the Château de Bonnefort until he was old enough to embark on his military career. His father prevented him from seeing his mother for 13 years while she was the king's mistress. Consequently, he had little to no relationship with her prior to his presentation at court. By 1683, he had been presented at court and his father had bought a commission of lieutenant for him.

At court, he quickly befriended his half-siblings including the two sons of Louis XIV by his mother: the Duc du Maine and the Comte de Toulouse. Yet, despite his best efforts, Louis XIV never warmed to him personally but the king did come to appreciate his professional talents. Perhaps the king was worried that Louis Antoine took after his father and would thus become a problem by his public demonstrations of outrage at the king's behaviour. He even entered the society of the king's only legitimate son, the Grand Dauphin, through his marriage to Julie Françoise de Crussol in 1686.

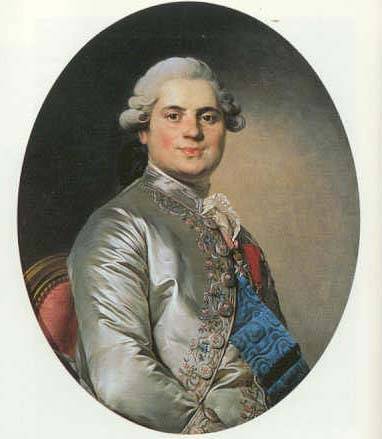

|

| Louis Antoine |

Ironically, Louis Antoine did not find royal favour until the death of his mother. It has been suggested that Louis XIV did not appreciate the presence of his former mistress' legitimate son as it brought back unpleasant memories of the fact that she had effectually had to abandon her legitimate children for those the king himself had sired. Not only did he inherit several of the estates bestowed upon Madame de Montespan by the king. He used his natural aptitude for both management and diplomatic tact to eventually win over the king who gave him the post of head of his buildings department. He managed so well that the king even appointed him to the regency council that took over after the death of the king.

Louis Antoine would eventually also be granted a ducal title. In 1711 he was officially made the Duc d'Antin. Following his mother's exit from the court in 1691, the two does not appear to have kept much in contact.

His marriage had resulted in two sons: Louis and Pierre. Louis inherited the title and lands of his father, as per law, while Pierre was handed over to the church. The Montespans being Catholics, Pierre was prohibited from having children but Louis did.

Having been married to Marie Victoire de Noailles who - oddly enough - also gave her husband two sons: Louis and Antoine. The same pattern took place with Louis inheriting the goods of the family; Antoine, however, died without marrying or fathering children - although he did not enter the church. The union between Louis and Françoise Gilonne de Montmorency could have ended the line. Four children were born to them, three being girls: Julie Sophie, Louis, Marie Françoise and Julie Magdaleine. Louis himself died at the age of 36 while his son, also Louis, died without having either married or having children.

As Julie Sophie became an abbess, the family only lived on in the female line. Marie Françoise married into the Durfort-family while Julie Magdaleine had the Duc d'Uzès. Interestingly, the current Duc d'Uzès is descended from her.

.jpg?mode=max)