Like his predecessor, Louis XV had a keen interest in women - however, unlike his great-grandfather, he was not wont to publicly recognise his illegitimate children. While it is well-known that he fathered several children out of wedlock - it would be difficult not to considering the number of mistresses he had and the state of contraceptions - few have been recorded to history in more than a few words. Of these children, one in particular stands out: Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara.

By 1755, Louis XV was 45 years old and considered to be one of the handsomest men at his own court. It was there that he would have encountered Françoise de Chalus, Duchesse de Narbonne-Lara, who served as a lady-in-waiting to Louise Élisabeth, the king's daughter. By 1749, this eldest daughter of the monarch had become the Duchess of Parma and was visiting her native country - in her entourage was a Spanish Grandee with the title of Comte de Narbonne-Lara. Jean François - as he was christened - would marry Françoise de Chalus in 1749.

|

| Françoise de Chalus as a young lady |

As Louise Élisabeth was due to return to her husband's duchy of Parma in 1755, the couple accompanied her. Whether Françoise knew it yet or not cannot be ascertained but by the time they arrived in Parma, she found herself to be pregnant. Typically, this would hardly have been surprising for a young lady who had been married for six years but the pregnancy still set tongues wagging at both the courts of France and Parma. The thing was that eight years prior - in 1747 - Jean François had served as a soldier in the War of the Spanish Succession. While there, he had sustained an injury which left him "unable to have children" - more specifically, he had received a gunshot to his lower abdomen. This was far from mere speculation as Jean François himself had included it in a petition to Louis XV of 1747. Yet here he was, with a pregnant wife.

It was soon speculated that the real paternity lay with the king. When the child was born in August 1755, he was baptised Louis.

There is another aspect to this story which warrants a closer look. Louis was not Françoise's first child - she had an older son by the name of Philippe who was also born after his "official" father sustained his injury, more specifically in 1750. As it was widely rumoured that Madame de Narbonne-Lara had been a minor mistress to the king, it is possible that Philippe, too, was the king's child.

But why, then, was it only Louis who became the centre of the courtiers' attention?

The brief answer would be: his looks. Throughout his life it would be remarked that the young Comte de Narbonne-Lara had an uncanny resemblance to the king - something that his elder brother does not appear to have shared. It should also be remembered that Philippe's father might not have been the king at all.

Some has argued that the later bestowal of the title of "Comte de Narbonne-Lara" is an indication of royal favour. However, it should be remembered that the child's official father was the duke of that same name. It would therefore not be unusual for his son to have a similar title.

| Louis, Comte de Narbonne-Lara in his older years |

What could be seen as a sign of the child(ren's) royal paternity is the extraordinary good fortune of Jean François following his injury. Besides being allowed to marry a frenchwoman with a substantial position at court, he was later showered with royal favours - especially after the births of Philippe and Louis. His war injury excluded him from reentering active military service yet he was given the rank of colonel and appointed to the king's son-in-law's personal household. Later, when the young Louis was seven years old, Jean François was further rewarded for his complaisance with two major distinctions: the rank of Maréchal and the title of Duc de Narbonne-Lara.

This is quite the astonishing rise for a man such as Jean François. To be sure, he was from an ancient noble family and had certainly made sacrifices during his military service to the king. However, this could easily be said of several other men at court who never received equal rewards. Considering that Louis XV was well-known to have enjoyed his wife's favours, it seems more likely that these benefits were a repayment for graciously remaining quiet on what was practically an open secret.

From a purely logistical point of view, it is possible that the king was indeed the father of the two children. While Madame de Narbonne-Lara was officially settled in Parma, she did travel extensively between Paris and Parma. The timing, too, adds to the probability. Madame de Pompadour had recently withdrawn her more intimate favours and the king had not yet begun seeing the stream of unknown bourgeoise women that would later be so ruinous to his reputation. This would mean that there was an open position for a young woman - as long as she accepted that she would not become the official mistress. Perhaps Madame de Narbonne-Lara had hopes of replacing Pompadour in the king's affection - perhaps not. Either way, Madame de Pompadour might have accepted that she served as a distraction, knowing that she would - eventually - be obliged to return to Parma.

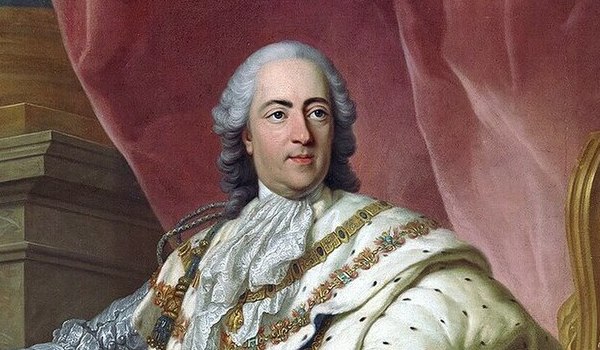

|

| Louis XV |

Some of the more scandalously inclined courtiers were quick to speculate in wilder terms as to the paternity of Louis de Narbonne-Lara. Even to a modern reader, the stories concocted by such persons seem astonishing. Some were certain that Françoise was not the mother at all but that she had agreed to pose as such in return for royal favours. Those supporting this theory claimed that the child was the offspring of one of the king's daughters - some even went so far as to say that the child was the result of an incestuous affair between the king and one of Mesdames.

Others claimed that the dauphin or even the Duke of Parma had fathered the off-spring which - in either case - would be a terrible embarrassment to the royal family. Either one of these theories seem far fetched to say the least; Mesdames were in the public eye constantly and a pregnancy would certainly not have gone unnoticed. While both the dauphin and the Duke of Parma technically could have fathered the child the question would be - why go to such extents to hide it? After all, this was an age where illegitimate children of high-born princes was hardly a foreign concept. Even if the Duke of Parma would have been eager not to anger his august father-in-law, surely it would have been easier to ship the child off to some family far away from court.

Finally, there is another indication that Louis XV truly was the father. While they had been born in Parma, Louis and Philippe were taken back to Versailles where he would not only be given a lavish education - alongside Mesdames no less - but would be attached to their households afterwards. No other child was allowed to share in the royal children's upbringing to such an extend. But it was the children's baptisms that seemed to cement their royal parentage. Rather than being baptised in the chapel, they were taken to the king's private cabinet - something that had previously been reserved for a king's illegitimate children.

The very intimacy he enjoyed with the royal family was truly something out of the ordinary. Besides being a frequent visitor in the apartments of Mesdames, he was also welcomed by the dauphin. Even after the outbreak of the revolution forced Mesdames to flee to Rome, he would accompany them and return as a staunch monarchist.

Both Louis and Philippe survived the revolution, dying in 1813 and 1834 respectively.