Madame Élisabeth, sister to Louis XVI, was 29 years old when her brother mounted the scaffold. She had been born Élisabeth Philippe Marie Hélène de Bourbon to the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand and his Saxon wife, Marie Josèphe. Since then she had spent her life at the court of Versailles and the splendid palaces belonging to her family.

30 years later she found herself in the Temple, a prisoner of a violent revolution. Yet, her gender marked her as being of little threat to the regime struggling to be born; after all, the Salic law which had ruled in France for centuries banned females from ascending to the throne. Therefore, Madame Élisabeth was not included in the indictment issued against her sister-in-law, Marie Antoinette. Initially it was decided that Élisabeth was to be exiled after the queen's trial. Therefore, she was not executed alongside either her brother or her sister-in-law.

|

| Madame Élisabeth |

On 9 May 1794, she was suddenly taken from the Temple and transferred to the Conciergerie. Unbeknownst the her, the regime had changed its mind and now fully intended to place the woman known now merely as the "sister of Capet". For the final time, she embraced her niece, Marie Thérèse before being brusquely informed that she would not return.

Rather than being taken to a cell to await further instructions, Madame Élisabeth was taken before the Revolutionary Tribunal. It would be the beginning of a short trial, lasting just two days. The charges laid against her were dire indeed: corresponding with enemies of the state, funding émigrés, counselling Marie Antoinette, assisting the king's flight to Varennes and encouraging anti-revolutionary activities.

The young woman met her accusers with a calm dignity and plainly denied any of the charges; without losing her temper, she informed her accusers that Marie Antoinette had had no secret councils and that she therefore could not possibly have assisted in them.

|

| Élisabeth with her brother on 20 June 1792 - she would later be condemned for providing assistance to wounded soldiers during the violent demonstrations |

The trial was a farce typical of the Revolutionary Tribunal. Madame Élisabeth was denied a proper defense attorney; the man who had been appointed to act as such, Claude-François Chauveau-Laofarde, was intentionally misled by the Tribunal. For instance, he was told that there was no need for him to confer with his "client" as she were not to be tried any time soon - this turned out to be a direct lie as the princess was tried the very next morning. This meant that when Chauveau-Laofarde scrambled to court, he had not even met the woman he was defending.

Dressed in a red gown, Madame Élisabeth was one amongst 24 accused standing trial. It was remarked that her calmness affected those around her. It was very much a trial with a fixed result. The same questions were posed to her - and again she refused to take the bait. Even when Dumas - the man in charge of the trial - actively attacked her character and attempted to twist her words, she refused to meet his accusations with anything but rationality.

Élisabeth was not a fool - even if she had not known that her brother had gone to the scaffold following a trial much like hers, she must have known that the deck was stacked against her. None of her accusers made any attempt at hiding their obvious disdain for her. The verdict was expected: Madame Élisabeth - and the other 23 accused - were found guilty on all charges. In the same breath, it was decided that she were to be executed the next morning.

If anyone doubted that contempt held for her by the President of the trial, they needed only her him commenting: "There will be nothing preventing her fancying herself still in the salons of Versailles, when she sees herself, surrounded by this faithful nobility, at the foot of the holy guillotine".

|

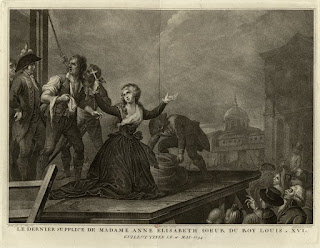

| Madame Élisabeth leaving for the scaffold |

Once the condemned were removed, Madame Élisabeth once again exerted herself to the comfort of her fellow-condemned. She had always been a fervently religious woman and now she encouraged those who were to die with her. She chose to rejoice in the fact that the Tribunal had not asked them to renounce their faith "only their miserable lives".

There appears to be some conjecture about when Madame Élisabeth was definitely informed of the death of Marie Antoinette. Later, Marie Thérèse would recall that they had heard her mother's sentence being cried out from the people walking beneath their windows but that they had refused to believe it. One account claims that Élisabeth had asked to see her sister-in-law after her sentencing only to be told that she had suffered the same fate. Another claims that it was only at the foot of the guillotine that she overheard a callous remark. Once it was noticed that the condemned bowed to her before their deaths, a spectator allegedly remarked that that they could "make their salaams to her all they wanted, she will share the fate of the Austrian".

|

| Madame Élisabeth, 1792 |

When dawn broke on 10 May 1794, the cart rolled up in front of the Concergerie. It was not large enough to transport them all, so they were split up. Madame Élisabeth were amongst the first to be loaded onto the cart and taken to the Place de La Revolution (formerly named for her grand-father, Louis XV); once there, she refused the executioner's help in getting down. The ire of the courtroom followed the former king's sister even to her execution. Due to the large number of people destined for the guillotine, a bench was erected for them to sit upon. As a final act of spite, Madame Élisabeth was scheduled to be the last to die - she was therefore subjected to watching every single one of her 23 co-condemned being beheaded. Amongst these were her friends and acquaintances.

Nevertheless, she still used the time left to her to fortify the people around her. It had been decided that the executioner would read one name at a time but the condemned were unaware of the order. She had garnered so much respect amongst them that each person either curtsied or bowed to her before mounting the steps; in return, she recited the Catholic prayer, De Profondis. Finally, it was her turn and she followed them up to the blood-stained scaffold. Once she had been strapped to the board with her arms behind her back, her fichu blew off leaving her shoulders exposed. Therefore, she returned to her executioner and calmly said "In the name of your mother, monsieur, cover me".

Those were the last words she said before the blade fell. Unlike at the executions of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette the thud of her head hitting the basket did not occasion the usual "Vive la republique" but rather silence. The king's sister - the same woman the poor had nicknamed "the good lady of Montreuil" - had always a good reputation, earned by her generous donations to the poor and her obvious devotion.

The remains of Madame Élisabeth was thrown into a mass grave in the Errancis Cemetery. Louis XVIII would later attempt to find the remains of his sister to rebury her in Saint-Denis - but in vain. Her bones are no longer there; instead, her skeleton was amongst those taken to the catacombs.

|

| Madame Élisabeth at the scaffold - cross in hand |

The people who shared her fate that day were - as can be seen, the de Lémoine family were eerily over presented:

Louis Bernadin Le Neuf, Comte de Sourdeval, aged 69

Anne Duwaes, aged 55

Anne-Nicole de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, Comtesse de Sénozan, aged 76

Charles Cressy Champnilon, aged 33

Claude Louise Angélique Bersin, Marquise de Crussol, aged 64

George Folloppe, aged 64

Louis-Pierre-Marcel Letellier, aged 21

Théodore Hall, aged 26

François Alexandre Antoine de Lémoine, Vicomte de Brienne, aged 36

Louis-Marie-Athanase de Lémoine, Comte de Brienne, aged 64

Denise Baurd, aged 52

Jean-Baptiste Dubois, aged 41

Antoine-Hugues-Calixte Montmorin, aged 22

Jean-Baptiste Lhoste, aged 47

Martial de Lémoine, aged 30

Antoine Jean François Megret de Sérilly, aged 48

Élisabeth-Jacqueline L'Hermite, Comtesse de Rosset, aged 65

Anne Marie Louise Thomas, aged 31

Françoise-Gabrielle de Tanneffe, aged 50

Anne Marie Charlotte de Lémoine, aged 29

Antoine Jean Marie Megret Detigny, aged 46

Charles de Lémoine, aged 33

Marie-Anne-Catherine Rosset, aged 44

Louis-Claude L'Hermite Chambertrand, aged 60